|

Morally Decadent Trickster Figures in Francophone Oral Daniel E. Noren

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Over the past quarter of a century, a group of creative modern-day Pléiade writers, poets, and linguists in Martinique have been intensely purposeful in fanning the flames of the Créole language, keeping it alive and fighting on the forefront of the battle against the Frenchification of this centrally-located island of the Lesser Antilles. The three contemporary “immortels” of Martinique: Dr. Jean Bernabé, Dr. Raphaël Confiant and Dr. Patrick Chamoiseau, have written what amounts to a manifesto for the Créole language and culture, Eulogy to Creoleness, of which the following quote is a good summation of the actual state of their struggle and reality of living every day under the Créole banner.

One very important manifestation of the Créole language are the many oral traditions extant that have come down from centuries of lived experiences, and cohabitation with Europeans (French) in a minority relationship, from the point of view of culture and language. Dr. Patrick Chamoiseau describes the oral tradition aspect of the culture in vivid detail in the following passage:

In her Preface to the Contes et legends des Antilles, Thérèse Georgel also writes a wonderful description of the Antillian story teller:

In the forward of his most delightful collection of orature (“oraliture”), Contes Créoles des Amériques (Creole Oral Traditions of the Americas), Dr. Raphaël Confiant of Martinique states that the trickster figure in the plantation society is primarily a survivor, without morals. This is an anomaly since orature traditionally has been used as an entertaining educational tool in Western culture, instructing children in proper conduct. It is through the medium of the trickster figure that children learn that greed, selfishness and pride lead to bad ends. In the European tradition we can note such childhood heroes as Reynard the Fox, (When Reynard Taught Wolf How To Fish, and the moral of the story, “She/he who wants all, loses all.”How Reynard Tricked Chantecler Into Singing For Him, “Don't be fooled by flattery.”), or Turtle (When Turtle Wanted To Travel To Far Off Lands, “Pride comes before a fall.”). Three thousand miles to the south-east in Congo (former Zaire, and previously the Belgian Congo), Turtle's main qualification for being a respected and venerated trickster is due to the fact that his whole being is driven by the whims of “mayèlè mabé” (from the original Lingala), literally translated as “bad wisdom”, though the linguistic fit implies the ultimate in a deceptive way of thinking, the supreme opportunist, having only one's most selfish interests at heart (much like Zaire's former president Mobutu, a product himself of the colonial environment, and the undisputed King of Zaire's tricksters). The polarity between these oral traditions (continental Europe, and the Francophone diaspora), we believe, is due to two very opposing and different cultural milieus; one of the colonizer (Africa) or “Planteur/Béké” (Plantation owner, Caribbean) and the other of the colonized (Africa) and slave (Caribbean). The trickster figure in Francophone oral literature beyond the “Métropole” is the mouthpiece of his/her social position, commenting on daily life in the plantation society, or under the strong hand of the colonizer. As Dr. Confiant points out, the most important aspect of life as a slave in that harsh system was daily survival. Thus, Compère Lapin (Brother Rabbit/Bre'r Rabbit) must be extremely selfish and look out only for number one. Compère Lapin is first and foremost a survivor, at the expense of everyone else if necessary, just the opposite of the Western world's notion that the good of the many outweighs the good of the few. Two thousand miles across the ocean in Senegal, Hampâté Bâ's trickster hero, the little hare “Petit Bodiel” (just like Leuk le lièvre) is given the following advice about being a successful and crafty individual, infused with deceptive personality traits. First he wants to learn:

Following is more advice and the experiences that Petit Bodiel goes through in the process of qualifying for tricksterdom, taken from Hampâté Bâ's Petit Bodiel, and quoted from a paper I gave at the Duquesne Language Conference in Pittsburgh in 1995:

The trickster figure in Francophone oral literature is the mouthpiece of his or her generation, and it is their eyes that provide us with a lens through which we can understand the plight of the colonized peasant or hopeless daily existence of the slave; it is history through the eyes of the “wretched of the earth” as opposed to those in power. Jean-Paul Sartre's following statement from his introduction to Frantz Fanon's The Wretched of the Earth (Les Damnés de la terre ) is powerfully appropriate:

In Jan Vansina's Kingdom's of the Savanna, he states

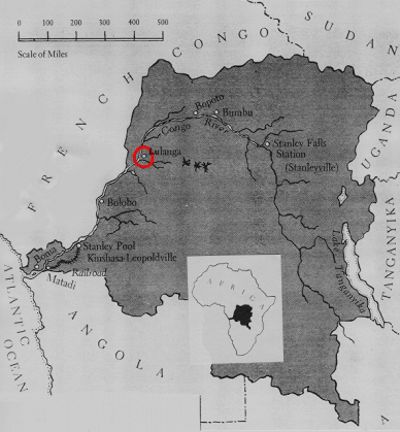

The following story, recounted to my brother in French, in Kinshasa, Zaire in 1985 is a prime example of a colonial era oral tradition, with the unique view from the colonized perspective. The trickster in the story is Turtle (“Koba,” in Lingala), the most common and most successful trickster of Central Africa. * Turtle (in my opinion) represents the common Congolese peasant under the Belgian colonial regime. The pig in the story, “Cochon” in French represents the “Colon” or colonial. “Colon” obviously has a double entendre and the proximity to the word “Cochon” is perfectly appropriate (“salaud de colon”) for this classic story of Colonized vis à vis Colonizer. The story opens up with Turtle arriving at his mud hut in a flurry and informing his wife that he has just had an encounter with Pig (Cochon) in the market. Pig reminded him about a large debt Turtle owed him, and warned Turtle that he was coming to the former's house to collect a significant sum of money owed him by Turtle (much more than Turtle had). *J.P. Hulstaert, a Belgian priest in the Mbandaka area of Congo (right on the Equator) where the dominant ethnic group is the Mongo, collected hundreds of oral traditions during his forty-year career there. One of his works, Contes Mongo, comprises some 1'500 stories of which Turtle is clearly the most successful, deceptive, witty, and venerated trickster of the region. Turtle comes up with a plan that cannot fail. He will transform himself into a table by turning over on his back, and his wife will use his flat, hard belly as a table, where she will be crushing peanuts with a flat stone to make peanut butter. Pig arrives in a huff and demands Turtle's wife what has become of her husband. Turtle's wife responds that he just went out in the “zamba” (bush) to relieve himself. Pig, angered beyond reason, grabs the nearest thing, the “table” (actually Turtle) and throws it out the door with a tremendous heave. It lands way out in the zamba. A few seconds later Turtle comes casually strolling in and nonchalantly greets Pig who immediately demands his money. “The money I owe you?” Turtle demands. “O.K., no problem, let me go get it from the underside of the table, where I always hide my money.” Of course the table is gone, and Turtle “discovers” that Pig has hurled it out the door in his fit of rage. The blame and responsibility are thus cleverly shifted to Pig. Pig immediately runs outside into the zamba around Turtle's hut and begins rutting around with his nose, in the brush and in the mud, like Pigs do to this day, looking for the table and money hidden under it, which he will never find. The first observation one can make about this story is that it is clearly a new version of La Farce de Maître Pathelin (probably the most famous Medieval farce in the French Cannon), adopted to the colonial context, a piece of colonial literature that has been absorbed into the Congolese culture as a sort of parody about the Belgian colonials where colon = cochon. We would argue however that it is at heart an oral tradition of Congo because it is clearly an origin story such as is referred to by Jean-Pierre Makouta-Mboukou:

The story most likely ended in the following manner in its original version:

The original version of the story may be lost, but it most certainly would have been an origin story, explaining a curiosity in nature, why pigs use their noses like that to rut around, and most likely referring to wart hogs, or the famous Central African red forest hog, having been observed in nature by the hunters stalking them for fresh meat. In the original story there was most likely a false trickster figure to oppose Turtle, perhaps Leopard, Civet, or Monkey, and the main dynamic of the story would not have had to do with money (a European import). The interesting thing to note about the hybrid story is that the origin aspect of the story is no longer the central purpose and focus of the story, but rather the moral of the story which is that: “It is perfectly fair and just to steal from the ‘Colons', if you can get away with it.” After all, they are just dirty animals who have been rutting around and depleting the country of raw materials such as gold, diamonds, rubber, ivory and copper at the expense of the Congolese for the past 100 years. Francophone oral literature is a powerful insider communication tool of how the common villager or peasant/slave must live and survive with dignity, given the hostile and uncooperative environment of the colonizer/planteur, where he/she exists in a continual state of discrimination and humiliation. Ironically, if there is one word to sum up the ultimate, worshipped and venerated act of the hero/trickster of the Caribbean and Africa during the colonial and plantation society era, it is deception. Ever since Diego Cão sailed down the West coast of Africa and “discovered” the mouth of the Congo River in 1483, and the slave trade that followed, an unsurprising attitude of “each man for himself and God against all” has ensued. An interesting story that began circulating in Zaïre, as far as we can tell during the mid 1980's, illustrates this acquired fatalistic way of thinking well, and from the orientation of the insider's observation, once again. It was near the end of Mobutu's thirty year reign of pure tyrannical despotism in an economy that had become known as a Kleptocracy, where Mobutu was the chief thief. Mobutu had attempted to deify himself in the early seventies by calling himself the “Fondateur” of the country, and a kind of benevolent father/king figure, wearing the traditional leopard skin hat of the Bakongo kings and carrying a scepter made of ivory and ebony. To implement his Africanization policies and a return to authentic African traditions and ways of living, renouncing European values, he founded the MPR (Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution). MPR agents were assigned to villages throughout the country to aid in the dissemination of what amounted to the almost blatant worship of Mobutu. One of the MPR programs was “Salongo” (from the Lingala “Sala” , imperative form of the verb “work”, and “elongo”, together). The use of a Lingala word instead of a French word was clearly a purposeful choice, just as if a similar program were to be envisioned for Martinique and Creole would be the obvious choice to appeal to the grassroots population. Every Saturday a forced “Salongo” project was directed by all the village MPR “animateurs”. Ironically, the most common chore was the intense manual labor of the continual maintenance of the dirt road that ran through each village. Only those involved in export crop production like coffee benefitted by being able to sell their product to the trucks driving out to the processing sights. The following story recounts the predominant attitude of the Zaïrois towards the Mobutu years, himself a perpetuator of neo-colonialism. Turtle is the trickster in the story and represents the MPR “animateur”, who is the incarnate symbol of Mobutu at the village level. The story opens up on a typical Saturday morning, at the crack of dawn, in the mid 1970's. Turtle is out and about rallying the animals to come together to do their weekly “Salongo”. The first animal that arrives, still rubbing his eyes from sleepiness, is Cockroach. Turtle indicates the part of the road where Cockroach should work and dig, and so he goes and begins working. Cockroach notices Chicken coming to work (most feared enemy of Cockroach) and runs and hides behind a tree. Chicken arrives and asks Turtle if she is the first one to come to Salongo. Turtle answers that Cockroach has preceded her and that he is hiding behind that tree over yonder. Chicken runs to the tree and gobbles up Cockroach, her favorite dish. Chicken begins working and notices Civet Cat coming to work, so she hides behind the same tree. Civet Cat asks the same question that Chicken did, and Turtle answers the same way, in the obvious parallelism style of the oral tradition, so Civet runs behind the tree and devours Chicken (the favorite prey of Civet Cat). Then Leopard comes to Salongo, and the same scenario unwinds and Leopard eats Civet Cat. Next a man comes and kills Leopard. Finally God comes, and kills the man. The moral of the story is that nobody wins under the Mobutu regime, which was very true. Mobutu was by far the greatest and supreme Trickster of Zaïre, who was able to amass a fortune of 8 billion dollars while the majority of the population of “Zaïrois” did not even have one pair of shoes to their name. In another story that clearly comes from the Belgian colonial years, 1899 – 1960, Turtle represents the common villager who has no rights or respect under King Leopold's administration of the “Congo Free State,” and thus has to seek equality through trickery, to go out and take it by his own wits since they will not grant it to him. The following passage, once again, is taken from my paper given at the Duquesne Foreign Language Conference:

Première Partie du Conte

Deuxième Partie du Conte

The cruelty and harshness of the environment wherein the trickster lives and breathes causes him to be deceptive and an opportunist. The story just mentioned was actually an example of how an erroneous colonial policy is remembered in the oral tradition, affirming John Vansina's earlier quote. The Belgians were actually involved in cutting off hands of Congolese people, as a form of punishment for not bringing in their daily rubber quota (a couple kilos every day, collected from the forest), and for other reasons as well. The account of these atrocities has been well documented by Edmond Morel in his work Red Rubber, the story of the rubber slave trade flourishing on the Congo River in the year of our lord 1906. Quoting from “The Testimony of the Kodak”, 10 March, 1904, Lake Mantumba, in the Lulanga region, Belgian Congo, we find that cutting off hands was a common occurrence, even on the sides of the “pirogue” (dugout canoe) like in the story of Turtle:

The woman sitting down was an old creature named Eyeka. I knew her well. She was the sister of Eloba 's mother-they came from the town of Mwebi, which is on the west shore of Lake Mantumba. Mwebiwas attacked by the (government) troops from Bikoro, in pursuance of the customary punitive policy for not working rubber (not procuring a daily quota). Eyeka more than once told us in the Mission how she lost her band. When the soldiers came to Mwebi, she said, they beard a bugle blow, and she and her son and many people fled. They ran as shots were fired, and her son fell by her side. She fainted and fell down too. Then she felt some one cutting at her wrist , and she was afraid to move, for she knew that if she moved her life would be taken. In the opinion of the State the soldiers, in killing game for food, wasted the State cartridges, and in consequence the soldiers, to show their officers that they did not expend the cartridges extravagantly on antelope and wild boar, for each spent cartridge brought in a human hand , -the hand of a man, woman or child. These hands, drying in the sun, could be seen at the government posts along the river (Congo River).

In conclusion, it is not difficult to understand why the trickster figure living in an oppressive environment and under the iron fist of the colonizer, dictator (Mobutu), or the slave master/béké must become a cruel, deceptive, and sadistic individual himself simply to survive; yes… survival, the most primal drive of humankind. It is out of that dehumanizing environment that the trickster figure of the Francophone diaspora beyond the “Métropole” has evolved. Unfortunately, the dehumanizing dynamic works both ways, as Aimé Césaire has so poignantly noted in his Essai sur le colonialisme, and maybe explains why we find so much crime, cruel acts, and deceptive ways of thinking in France and in our current Western “Civilization,” for the French are not the only imperialists in the world historically and contemporaneously speaking. Quoting Césaire:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| |